Weaponizing social media

Trolls, bots, lulz, infowars and other moods of the modern networked ape

October 21, 2019 — January 15, 2023

Content warning:

Discussion of terrorism and hate speech

I now regret using weaponized in the title of this notebook, because it, I think implies that emphasises the intent large coherent actors (famously “Russian propaganda”) but while that may be important, the general adversarial nature of the mediasphere in which we are all combatants seems important even if it has no coherent intent. Too late now I guess. Also this notebook has lost cohesion and turned into a link salad. It would be more valuable if it analysed and compared some theses; in this topic area is we need fewer link lists and more synthesis one where some synthesis would actually help.

Memetic information warfare on the social information graph with viral media for the purpose of human behaviour control and steering epistemic communities. The other side to trusted news; hacking the implicit reputation system of social media to suborn factual reporting, or to motivate people to behave to suit your goals, to, e.g. sell uncertainty.

News media and public shared reality. Fake news, incomplete news, alternative facts, strategic inference, general incompetence. kompromat, agnotology, facebooking to a molecular level. Basic media literacy and whether it helps. As seen in elections, and provocateur twitter bots.

Research in this area is vague for many reasons; It is hard to do experiments on societies at large for reasons of ethics and practicality for most of us. Also, our tools for causality on social graphs are weak and it is hard. There are some actors (nation states, social media companies) for which experiments are practical, but they have various reasons for not sharing their results. But we can get a long way!

But for now, here is some qualitative journalism from the front lines.

Coscia is always low-key fun: News on Social Media: It’s not Real if I don’t Like it.

Toxic-social-media doco The Social Dilemma was a thing, although not a thing I got around to watching. Was it any good?

Renee DiResta, The Digital Maginot Line related to insurgence economics argues that performative search for bad actors is insufficient because it misses the worst actors:

Information war combatants have certainly pursued regime change: there is reasonable suspicion that they succeeded in a few cases (Brexit) and clear indications of it in others (Duterte). They’ve targeted corporations and industries. And they’ve certainly gone after mores: social media became the main battleground for the culture wars years ago, and we now describe the unbridgeable gap between two polarized Americas using technological terms like filter bubble.

But ultimately the information war is about territory — just not the geographic kind.

In a warm information war, the human mind is the territory. If you aren’t a combatant, you are the territory. And once a combatant wins over a sufficient number of minds, they have the power to influence culture and society, policy and politics. […] The key problem is this: platforms aren’t incentivized to engage in the profoundly complex arms race against the worst actors when they can simply point to transparency reports showing that they caught a fair number of the mediocre actors.

If correct this would still leave open the question of low-key good-faith polarization by sub-standard actors, which no one seems to be tackling.

Epsilon Theory, Gell-Mann Amnesia

Michael Hobbes, The Methods of Moral Panic Journalism

Master List Of Official Russia Claims That Proved To Be Bogus lists some really interesting incidents in the Trump-administration era media reporting, that make the entire press corps look pretty bad.

Just 12 People Are Behind Most Vaccine Hoaxes On Social Media, Research Shows

Elkus on information/science/media dynamics in the age of crisis

More Elkus, Twelve Angry Robots, Or Moderation And Its Discontents

The Radicalization Risks of GPT-3 and Neural Language Models

Techcrunch summary of the Facebook testing debacle

[…] every product, brand, politician, charity, and social movement is trying to manipulate your emotions on some level, and they’re running A/B tests to find out how. They all want you to use more, spend more, vote for them, donate money, or sign a petition by making you happy, insecure, optimistic, sad, or angry. There are many tools for discovering how best to manipulate these emotions, including analytics, focus groups, and A/B tests.

Fun keywords:

- parasocial interaction, the way our monkey minds regard remote celebrities as our intimates.

- …

Sophie Zhang, I saw millions compromise their Facebook accounts to fuel fake engagement, raises an interesting point, which is that people will willingly put their opinions in the hands of engagement farms for a small fee. In this case it is selling their logins, but it is easy to interplolate a continuum from classic old-style shilling for some interest and this new mass-market version.

1 Fact checking

As Gwern on points out, Littlewood’s Law of Media implies the anecdotes we can recount, in all truthfulness, grow increasingly weird as the population does. In a large enough sample you can find a small number of occurrences to support any hypothesis you would like.

[This] illustrates a version of Littlewood’s Law of Miracles: in a world with ~8 billion people, one which is increasingly networked and mobile and wealthy at that, a one-in-billion event will happen 8 times a month.

Human extremes are not only weirder than we suppose, they are weirder than we can suppose.

But let’s, for a moment, assume that people actually have intent to come to a shared understanding of the facts reality, writ large and systemic. Do they even have the skills? I don’t know, but it is hard to work out when you are being fed bullshit and we don’t do well at teaching that. There are courses on identifying the lazier type of bullshit

- Calling bullshit.

- Adi Robertson, How to fight lies, tricks,and chaos online

and even courses on more sophisticated bullshit detection

Craig Silverman (ed), Verification Handbook For Disinformation And Media Manipulation.

Will all the billions of humans on earth take such a course? Would they deploy the skills they learned thereby even if they did?

And, given that society is complex and counter-intuitive even if we are doing simple analysis of correlation, how about more complex causation, such as feedback loops? Nicky Case created a diagrammatic account of how “systems journalism” might work.

-

Welcome! This is an online resource guide for civil society groups looking to better deal with the problem of disinformation. Let us know your concerns and we will suggest resources, curated by civil society practitioners and the Project on Computational Propaganda.

fullfact is a full-time fact checking agency in the UK, who do fact checking and reports such as Tackling misinformation in an Open Society

The previous organisation I found via Data Skeptic Podcast’s Fake News Series

An amusing portrait of snopes

Facebook’s Walled Wonderland Is Inherently Incompatible With News

Unfiltered news doesn’t share well, not at all:

- It can be emotional, but in the worse sense; no one is willing to spread a gruesome account from Mosul among his/er peers.

- Most likely, unfiltered news will convey a negative aspect of society. Again, another revelation from The Intercept or ProPublica won’t get many clicks.

- Unfiltered news can upset users’ views, beliefs, or opinions.

Tim Harford, The Problem With Facts:

[…] will this sudden focus on facts actually lead to a more informed electorate, better decisions, a renewed respect for the truth? The history of tobacco suggests not. The link between cigarettes and cancer was supported by the world’s leading medical scientists and, in 1964, the US surgeon general himself. The story was covered by well-trained journalists committed to the values of objectivity. Yet the tobacco lobbyists ran rings round them.

In the 1950s and 1960s, journalists had an excuse for their stumbles: the tobacco industry’s tactics were clever, complex and new. First, the industry appeared to engage, promising high-quality research into the issue. The public were assured that the best people were on the case. The second stage was to complicate the question and sow doubt: lung cancer might have any number of causes, after all. And wasn’t lung cancer, not cigarettes, what really mattered? Stage three was to undermine serious research and expertise. Autopsy reports would be dismissed as anecdotal, epidemiological work as merely statistical, and animal studies as irrelevant. Finally came normalisation: the industry would point out that the tobacco-cancer story was stale news. Couldn’t journalists find something new and interesting to say?

[…] In 1995, Robert Proctor, a historian at Stanford University who has studied the tobacco case closely, coined the word “agnotology”. This is the study of how ignorance is deliberately produced; the entire field was started by Proctor’s observation of the tobacco industry. The facts about smoking — indisputable facts, from unquestionable sources — did not carry the day. The indisputable facts were disputed. The unquestionable sources were questioned. Facts, it turns out, are important, but facts are not enough to win this kind of argument.

2 Conspiracy theories and their uses

see Conspiracy mania.

3 Rhetorical strategies

Sea-lioning is a common hack for trolls, and is a whole interesting essay in strategic conversation derailment strategies. Here is one strategy against it, the FAQ off system for live FAQ. This is one of many dogpiling strategies that are effective online, where economies of scarce attention are important.

4 Inference

How do we evaulate the effects of social media interventions? Of course, standard survey modelling.

There is some structure to exploit here, e.g. causalimpact and other such time series-causal-inference systems. How about when the data is a mixture of time-series data and one-off results (e.g. polling before and election and the election itself)

Getting to the data is fraught:

Facebook’s Illusory Promise of Transparency ish currently obstructing the Ad Observatory by NYU Tandon School of Engineering.

Various browser data-harvesting systems exist:

5 Automatic trolling, infinite fake news

The controversial GPT-x (Radford et al. 2019) family

GPT-2 displays a broad set of capabilities, including the ability to generate conditional synthetic text samples of unprecedented quality, where we prime the model with an input and have it generate a lengthy continuation. In addition, GPT-2 outperforms other language models trained on specific domains (like Wikipedia, news, or books) without needing to use these domain-specific training datasets.

It takes 5 minutes to download this package and start generating decent fake news; Whether you gain anything over the traditional manual method is an open question.

The controversial deepcom model enables automatic comment generation for your fake news. (Yang et al. 2019)

Assembling these into a twitter bot farm is left as an exercise for the student.

6 Post hoc analysis

Tim Starks and Aaron Schaffer summarise Eady et al. (2023): Russian trolls on Twitter had little influence on 2016 voters.

David Gilbert, YouTube’s Algorithm Keeps Suggesting Users Watch Climate Change Misinformation The methodology here looks, at a glance, shallow which is not to say it is not implausible.

Craig Silverman, Jane Lytvynenko, William Kung, Disinformation For Hire: How A New Breed Of PR Firms Is Selling Lies Online

One firm promised to “use every tool and take every advantage available in order to change reality according to our client’s wishes.”

Kate Starbird, the surprising nuance behind the Russian troll strategy

Dan O’Sullivan, Inside the RNC Leak

In what is the largest known data exposure of its kind, UpGuard’s Cyber Risk Team can now confirm that a misconfigured database containing the sensitive personal details of over 198 million American voters was left exposed to the internet by a firm working on behalf of the Republican National Committee (RNC) in their efforts to elect Donald Trump. The data, which was stored in a publicly accessible cloud server owned by Republican data firm Deep Root Analytics, included 1.1 terabytes of entirely unsecured personal information compiled by DRA and at least two other Republican contractors, TargetPoint Consulting, Inc. and Data Trust. In total, the personal information of potentially near all of America’s 200 million registered voters was exposed, including names, dates of birth, home addresses, phone numbers, and voter registration details, as well as data described as “modeled” voter ethnicities and religions. […]

“‘Microtargeting is trying to unravel your political DNA,’ [Gage] said. ‘The more information I have about you, the better.’ The more information [Gage] has, the better he can group people into “target clusters” with names such as ‘Flag and Family Republicans’ or ‘Tax and Terrorism Moderates.’ Once a person is defined, finding the right message from the campaign becomes fairly simple.”

But what’s often overlooked in press coverage is that ISIS doesn’t just have strong, organic support online. It also employs social-media strategies that inflate and control its message. Extremists of all stripes are increasingly using social media to recruit, radicalize and raise funds, and ISIS is one of the most adept practitioners of this approach.

British army creates team of Facebook warriors

The Israel Defence Forces have pioneered state military engagement with social media, with dedicated teams operating since Operation Cast Lead, its war in Gaza in 2008-9. The IDF is active on 30 platforms — including Twitter, Facebook, Youtube and Instagram — in six languages. “It enables us to engage with an audience we otherwise wouldn’t reach,” said an Israeli army spokesman. […] During last summer’s war in Gaza, Operation Protective Edge, the IDF and Hamas’s military wing, the Qassam Brigades, tweeted prolifically, sometimes engaging directly with one another.

Nick Statt, Facebook reportedly ignored its own research showing algorithms divided users:

An internal Facebook report presented to executives in 2018 found that the company was well aware that its product, specifically its recommendation engine, stoked divisiveness and polarization, according to a new report from The Wall Street Journal. “Our algorithms exploit the human brain’s attraction to divisiveness,” one slide from the presentation read. The group found that if this core element of its recommendation engine were left unchecked, it would continue to serve Facebook users “more and more divisive content in an effort to gain user attention & increase time on the platform.” A separate internal report, crafted in 2016, said 64 percent of people who joined an extremist group on Facebook only did so because the company’s algorithm recommended it to them, the _WSJ _reports.

Leading the effort to downplay these concerns and shift Facebook’s focus away from polarization has been Joel Kaplan, Facebook’s vice president of global public policy and former chief of staff under President George W. Bush. Kaplan is a controversial figure in part due to his staunch right-wing politics— he supported Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh throughout his nomination— and his apparent ability to sway CEO Mark Zuckerberg on important policy matters.

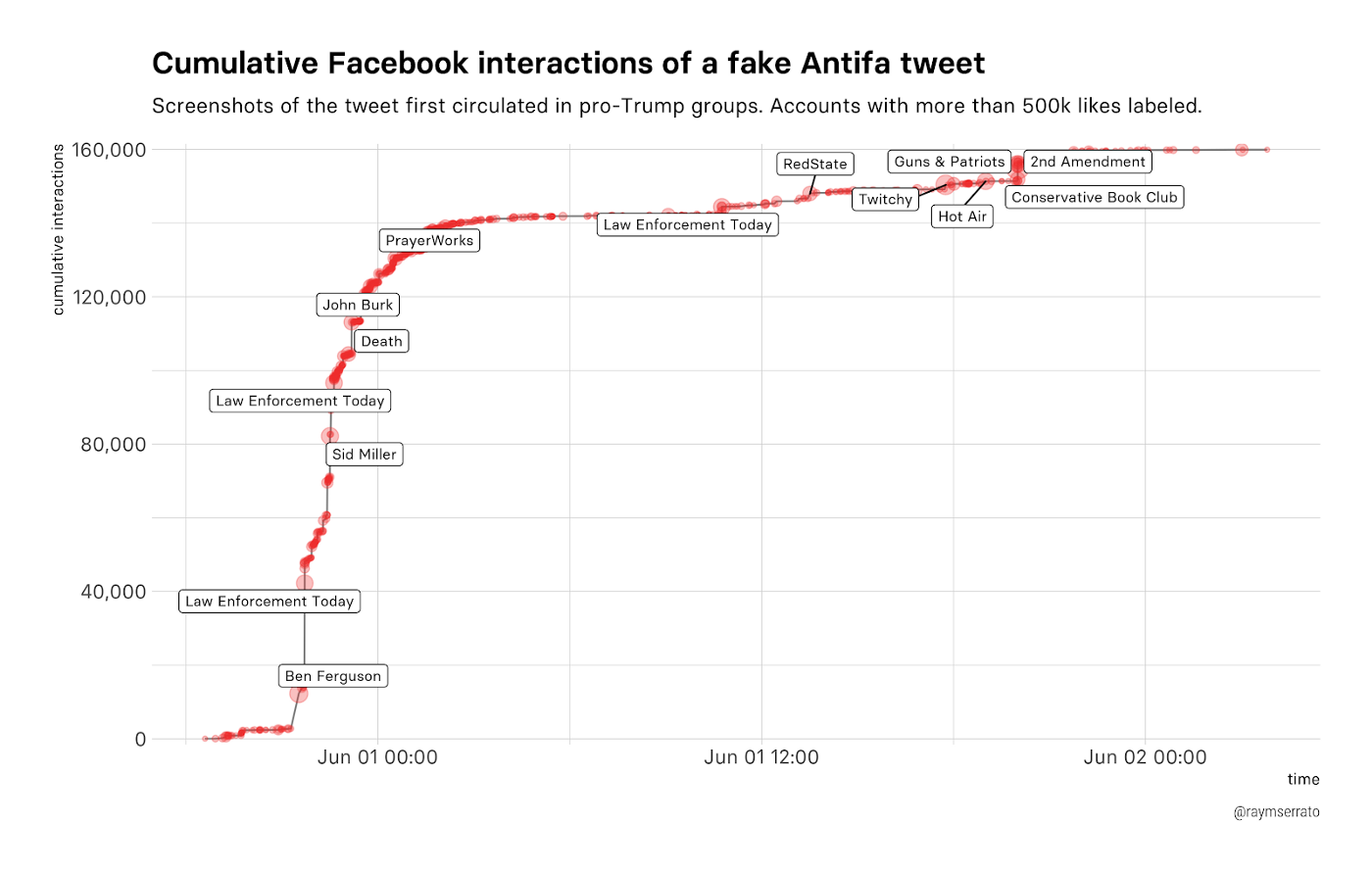

Ray Serrator documents the kind of dynamics that we should be aware of here. One false-flag tweet circulated by partisans gets far more exposure as a evidence of the vileness of the people it purports to come from than does the belated take-down of that tweet.

7 Incoming

The problem with raging against the machine is that the machine has learned to feed off rage

Liv Boeree summarises How the New York Times Broke Journalism

80% of the 22 million comments on net neutrality rollback were fake, investigation finds

Biggest ISPs paid for 8.5 million fake FCC comments opposing net neutrality

ISPs Funded 8.5 Million Fake Comments Opposing Net Neutrality

Joan Donovan, Research Director of Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, How Civil Society Can Combat Misinformation and Hate Speech Without Making It Worse.

Adam Elkus, Twelve Angry Robots, Or Moderation And Its Discontents

How the Far Right in Italy Is Manipulating Twitter and Discourse

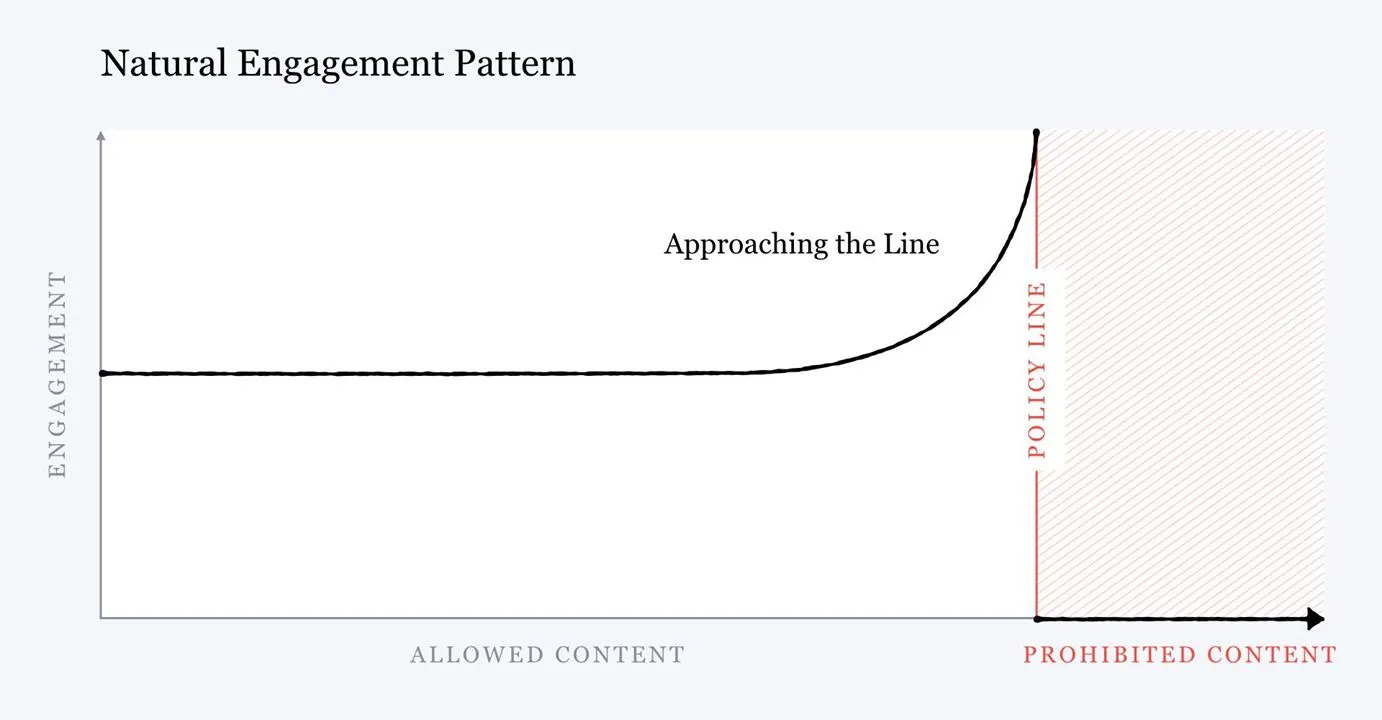

Facebook will change algorithm to demote “borderline content” that almost violates policies

Erin Kissane: Meta in Myanmar (full series) Very telling case study